35 Years of Miros’ Wave Radar: An Interview with Dr.ing. Øistein Grønlie

Miros was founded in May of 1984, with the Wave Radar as its flagship product. A lot has changed in the years that have passed since then, but there’s one familiar face that’s still making waves (and measuring them) at our HQ in Asker, just outside of Oslo, Norway.

Dr.ing. Øistein Grønlie has been a stalwart contributor to Miros’ story from the very beginning. Consequently, as part of Miros’ 35th birthday celebrations, we sat down with Øistein to get anecdotal and take a deep dive into the company’s past.

What can you tell me about the first team that was involved with Miros?

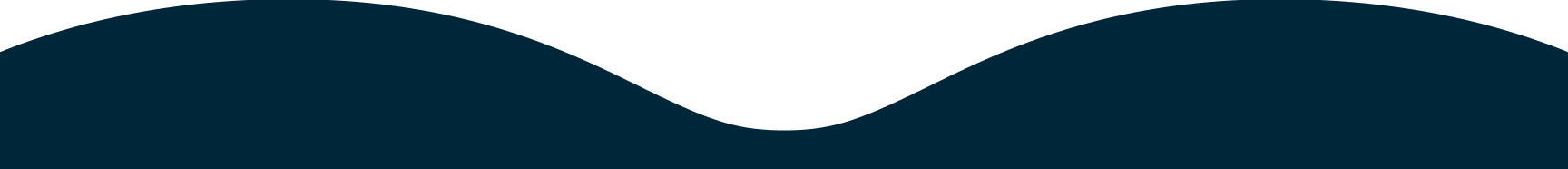

Well, there were only four of us. It was my former boss, Dagfin Brodtkorb, and myself. Then we had 2 software guys too. The development of the radar was based on ideas that came from a guy at the FFI, the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment, where I had worked after finishing university. His name’s Dag Gjessing and he had some ideas about developing a kind of pattern recognition using radar. The idea was to identify different types of aircraft based on the signature of the echo, but he also wanted to measure waves using the same method.

So Miros’ Wave Radar was based on governmental research?

Well, Dag Gjessing had been the head of a division of research at the FFI, but he applied for a program at the Royal Norwegian Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (NTNF, now the Research Council of Norway) which is a governmental institution funding research programs. He got his funding and began a research program to investigate making wave measurements using radar.

And that was the jumping-off point for Miros?

Yes, Dagfin Brodtkorb, who had been a colleague of mine at the FFI, was working at a company called Informasjonskontroll. He was then involved with trials implementing the radar for the research program. He was building the hardware of the radar, as well as developing the software. Based on the results of those trials, in 1984, Miros was founded. It was originally a subsidiary of Informasjonskontroll, specifically tasked with commercialising the Wave Radar.

What had been your experience with radar up to that point?

I had done my military service at the FFI for a year, then, since my background is telecoms, I started working with radar systems for military applications. I did that for 10 years before Miros. So I had some background in radar and processing before I was recruited to join Miros in ’84.

At the start of Miros I had no knowledge of ocean waves, only of electromagnetic waves.

I see. So you had a relationship to the technology, but not necessarily to the offshore industry. How did that come about?

At the time we had no relationship with O&G or the offshore industry whatsoever. That all started due to the fact that any company wanting to do business on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS) had to contribute in some way to the Norwegian community. So when we at Miros started further development of the Wave Radar, we did so with funding from Statoil (now Equinor).

So aiding the development of the science was the industry’s way of contributing to society?

Yes. Exactly.

What do you remember about the early days testing the equipment?

We made the prototype of the Wave Radar, partly supported by the mechanical workshop at the FFI and partly by the electronics lab at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim. They helped us to build the microwave unit.

The microwave unit on the first Wave Radar was made from radiolink components. That’s partly why we ended up at the 5.8 GHz frequency, which was also quite convenient because that frequency is in the so-called ISM band, so it’s designated for science and medical purposes anyway. As a result it was quite easy to get a license to operate within it.

It also happened to be a nice frequency band for the purpose of obtaining a suitable echo from the sea surface too.

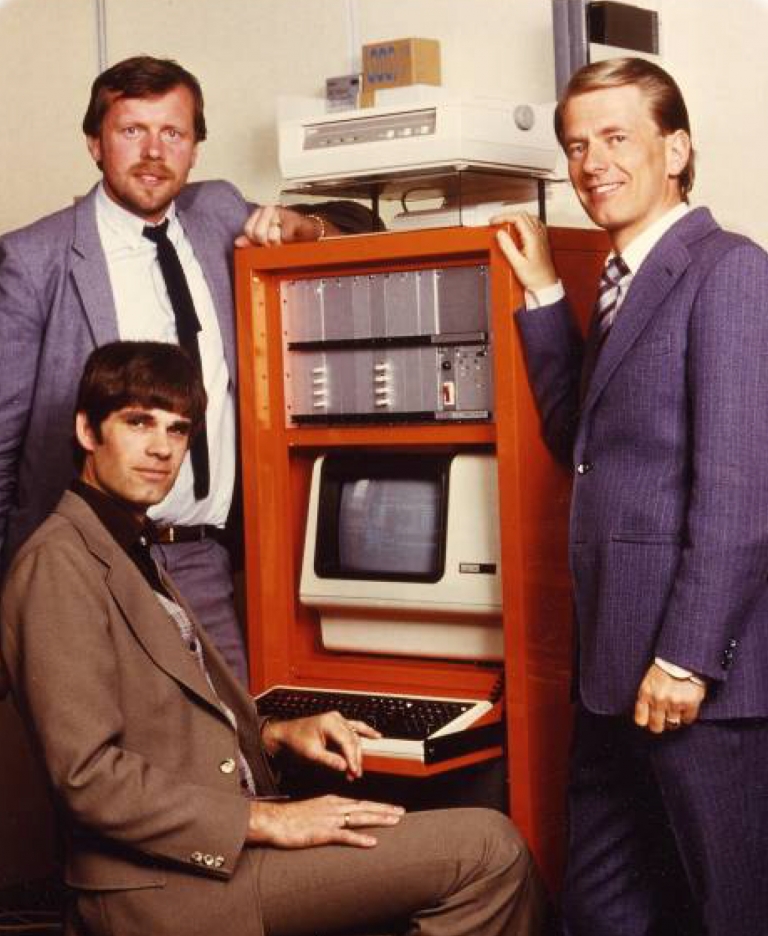

Then you lugged it to the top of a lighthouse in the middle of winter, correct?

Yes! We installed it ourselves. Of course, we couldn’t just be out there testing in calm weather. Winter is the season where you most likely get storms and high waves.

There were three of us at the lighthouse doing the installation work. Dagfin, myself and one of our software guys. Jan Wøien was his name. We made all the mechanical components that were required to attach the radar to the guard rail on the platform of the lighthouse. We took the microwave unit with the service antennas and all that up to the top. Then we had a wave buoy deployed off the coast of the lighthouse, measuring the waves and the currents to form comparisons. The rest of the equipment was installed downstairs. There were two equipment racks with the electronics tape unit for recording data, a micro computer – micro, it was quite large really.

When the first commercial application came, that was Statoil?

Yes, it was for a riser platform, part of the transport system from the Ekofisk oil field – in the middle of the North Sea – to Emden in Germany.

So when the first purchase order came through, it must have been quite a triumph.

Oh, yes it was. It was just one unit, but at the price of 1.7m NOK, it was quite a large amount of money. The price of the Wave Radar is half of that now, so taking the inflation into account, it has come down in price quite a lot.

I bet it weighs a lot less too!?

Oh the weight reduction is far more significant! The latest model that Miros’ Senior Development Manager, Torbjørn, is working on has seen a dramatic reduction in size and weight.

With the first purchase order, did you go to the platform to install the first commercial unit?

Yes I went to the platform myself, though various people were involved in the installation. You know, I was not accustomed to helicopter transport. That was a new experience. All the routines and procedures connected with that came later. At the time we could go there without having any training at all.

What are other memorable moments from the beginnings of Miros?

I spent a lot of time working out the theory. We measure something, we get an echo from the sea surface, we detect the Doppler shift of the echo which is caused by the motion of the water, and then that Doppler shift has to be processed and converted into the wave height and the wave spectrum. So there is a transfer function connecting the water velocity to the wave height and I spent a 18 months working that theory out.

A great moment was to actually measure the received data, analyse it, and see that it matched. To know that we managed to measure the waves like the wave buoy did. That was quite satisfying.

Plus, the radar has advantages when it comes to the operational cost. It’s far easier to maintain. It’s less costly that a floating buoy which get lost or stolen or whatever.

Presumably we are still using the same theory now?

Yes. The working principle is the same. It’s been refined though, and we have added a lot of functionality.

What has been your proudest achievement at Miros?

It’s very difficult to give a short answer. Honestly I’m thinking more of what I have not achieved rather than what I have. A great achievement would be to see that I have been able to contribute to the transfer of all this accumulated knowledge and experience to the people who are going to take care of the future.

I think we have some very knowledgeable and good people in the staff. You know, like Rune Gangeskar. I was actually involved in his Doctor’s degree back in 2003. And also in his Master prior to that. I was his supervisor in industry. I’m very pleased that he is here at Miros.

Rune is working on Miros Speed Through Water. That’s quite an exciting new development.

Oh yes. Speed Through Water is a different story. Rune is using a commercial navigation radar, the X-band, for that. It’s very interesting.

What was the biggest mistake you and the team made back at the start?

When we started we wanted to do everything ourselves. At the time we were thinking of keeping the production of all the electronics in house. Luckily we didn’t succeed in doing that, and it would have been a great mistake if we had. Sometimes you have to accept that there are third parties who are more capable of doing certain things than you are. You should stick to what you are good at. We stuck to measuring waves.

NORBIT make much of Miros’ hardware now, were they involved from the beginning?

NORBIT was a different company back then, called MicroDesign. They were building the first toll road system that was based on acoustic surface waves in Oslo. One of the guys in the development staff at MircoDesign was someone I knew from my home town of Trondheim, Steffen Kirknes, who formed NORBIT.

I should reiterate, Norway is not a very big place!

So NORBIT became involved quite early on. We had a product called Miris, which was the Miros ID system. It was created for use on the Ekofisk complex as a personal tracking system. I have a model of the transponder still.

The Ekofisk platform is a very large complex connected with bridges, so there are a lot of people moving about. In case of emergency, though, for evacuations and that sort of thing, everyone has to be accounted for. We set up gates with antennas and when passing that gate with this unit on, the people were detected. It was a bit like the toll road system, but with the potential for many people passing the gate at once, rather than single cars passing one by one.

So that was the first time Steffen was involved. The next time was when they made the transceiver for the RangeFinder!